By Hope McMath

It took 122 years for our nation to proclaim lynching a federal hate crime. Yesterday, March 29, 2022, President Joe Biden signed into law the Emmett Till Anti Lynching Act.

In the gathering of people who witnessed this historic act was a Black legislator who had dedicated his career to this work, the first Black Vice President, and family members of Emmett Till, the 14 year old Black boy abducted, beaten and murdered by a white mob in 1955.

These contemporary leaders and activists stand on the shoulders of people like Rep. George Henry White of North Carolina, the first Congressman to introduce anti-lynching legislation in 1900. They also fulfill the tenacious work of dozens of lawmakers who offered up such legislation 200 times over these 122 years.

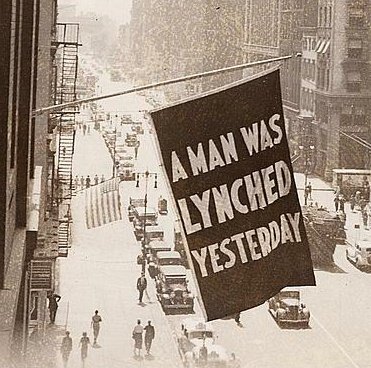

This moment brings to fruition the decades of effort and commitment to the cause by James Weldon Johnson. He not only wrote about the pervasiveness of the crime in songs, novels, and his autobiography, but also pushed for legislation while serving as a leader in the NAACP. The collective action he organized in 1917 known as the Silent Protest Parade saw 10,000 Black Americans dressed in white marching down 5th Avenue in New York City demanding action and proclaiming that their humanity and lives mattered. Even as legislation failed, Johnson refused to let the violence fall from the public gaze, flying a flag out the window of his offices everyday that a lynching was documented in America.

This moment brings to fruition the decades of effort and commitment to the cause by James Weldon Johnson. He not only wrote about the pervasiveness of the crime in songs, novels, and his autobiography, but also pushed for legislation while serving as a leader in the NAACP. The collective action he organized in 1917 known as the Silent Protest Parade saw 10,000 Black Americans dressed in white marching down 5th Avenue in New York City demanding action and proclaiming that their humanity and lives mattered. Even as legislation failed, Johnson refused to let the violence fall from the public gaze, flying a flag out the window of his offices everyday that a lynching was documented in America.

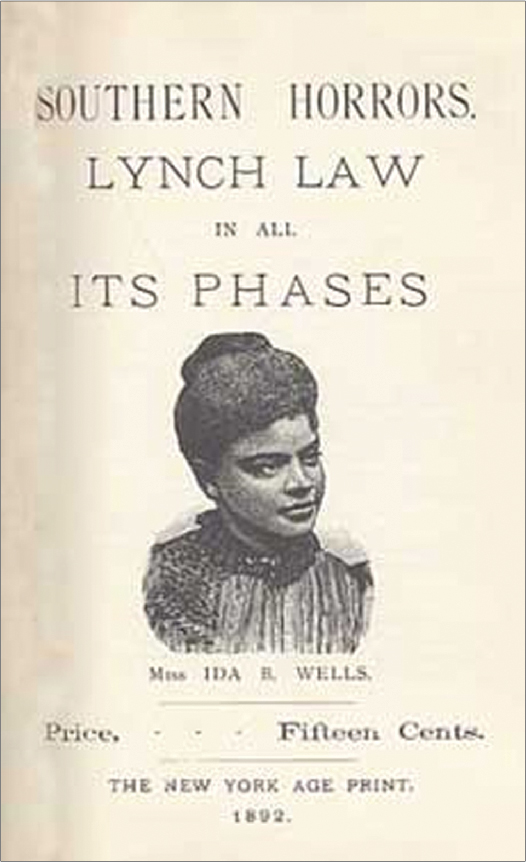

The bill signing made a reality of the pleas that Ida B. Wells lifted up in her writings and public speeches as a journalist, activist, and organizational leader. Her antilynching campaign found audience in spaces from the gatherings of the suffragette movement to the White House. The investigative excellence of Wells’ writings and presentations helped to build a movement and we owe her a huge debt of gratitude.

The bill signing made a reality of the pleas that Ida B. Wells lifted up in her writings and public speeches as a journalist, activist, and organizational leader. Her antilynching campaign found audience in spaces from the gatherings of the suffragette movement to the White House. The investigative excellence of Wells’ writings and presentations helped to build a movement and we owe her a huge debt of gratitude.

Those who came together for yesterday’s signing also extend the tireless work of Bryan Stevenson and all who have put their hands to the work of the Equal Justice Initiative over the past couple of decades – raising awareness of the truth of racial terror lynching and its connection to the scourge of mass incarceration and state sanctioned violence that continues to impeded our country’s progress.

Maybe most importantly, the signing of the Emmett Till Anti Lynching Act has been fueled by the blood of more than 4,000 victims of lynching and the fissures this racial terror created in the lives of families, communities, and the nation.

The men, women, and children murdered because of the color of their skin will never receive justice. Those who perpetrated the hangings, shootings, and burnings were never held accountable. Those who gathered as celebratory crowds to witness the murders were never held accountable. Those who wore the badge of security who refused to protect, prosecute, or too-often participated in the mob violence were never held accountable.

“From the bullets in the back of Ahmaud Arbery to countless other acts of violence, countless victims known and unknown, the same racial hatred that drove the mob to hang a noose brought that mob carrying torches out of the fields of Charlottesville just a few years ago — racial hate isn’t an old problem. It’s a persistent problem,” President Biden said during yesterday’s ceremony. “Hate never goes away, it only hides under the rocks. If it gets a little bit of oxygen, it comes roaring back out, screaming. What stops it? All of us.”

That it is still relevant is why laws like the one passed yesterday is necessary. It is why we must push back against efforts to weaponize teaching true history. It is why we must vote for progress, especially in this context as hundreds of Black Americans were lynched as they attempted to fulfill that right.

As we shine the brightest light possible on these truths it is important that we remember and honor those who have been its victims. Efforts like those undertaken by the Jacksonville Community Remembrance Project and 904WARD are part of the process of healing and truth telling.

As we shine the brightest light possible on these truths it is important that we remember and honor those who have been its victims. Efforts like those undertaken by the Jacksonville Community Remembrance Project and 904WARD are part of the process of healing and truth telling.

Today as I enter the space of Yellow House and breathe in our current exhibition Screams Echo: The Legacy of Lynching I will spend extra time at the ancestral space created to hold the soil collected at the sites of lynchings that took place in my city. It is intended to be a sacred space of reflection, created by the ritual of people gathering together to honor those who were so dishonored.

I will say their names:

Eugene Burnam

Edgar Phillips

Willie Washington

Bowman Cook

John Morine

Benjamin Hart

And I will remember the two men whose names are unknown to us today.

I will read aloud the words of James Weldon Johnson, a native son, inscribed on one of the powerful works of art by Marsha Hatcher. I will linger on the powerful installation of Erin Kendrick as she reminds us that the economic violence of redlining ran parallel to the physical violence. I will look with intention into the eyes of the parents, cousins and brother of artist Deja Echols as she asks us to see the beauty and power of family, while recognizing the cost of the daily threat that is all too real for the Black men in her life. I will repeat the words written by Bobbie O’Connor that remind us of the historic threads that connect the lynchings of last century to the death of the Trayvon Martin and Granny’s revelation that “times they are a changin’, then again they’re not.”

I will read aloud the words of James Weldon Johnson, a native son, inscribed on one of the powerful works of art by Marsha Hatcher. I will linger on the powerful installation of Erin Kendrick as she reminds us that the economic violence of redlining ran parallel to the physical violence. I will look with intention into the eyes of the parents, cousins and brother of artist Deja Echols as she asks us to see the beauty and power of family, while recognizing the cost of the daily threat that is all too real for the Black men in her life. I will repeat the words written by Bobbie O’Connor that remind us of the historic threads that connect the lynchings of last century to the death of the Trayvon Martin and Granny’s revelation that “times they are a changin’, then again they’re not.”

I will also double down on my commitment to doing what I can, from where I am, with what I have. What will you do? What will WE do?

Let us also move into this day with gratitude that we have FINALLY recognized this crime for what it is. While we cannot always change hearts and minds, we can pass policies that right some of our wrongs.

We cannot alter the past, but we can see it with clarity and turn that into fodder for a radical reimagining.

We welcome you to visit the Screams Echo exhibition between now and April 16th. Yellow House is open Wednesdays 12 – 7pm and Saturdays 11am – 2pm.